ON CAPPELENS FORSLAGS

CONVERSATIONAL LEXICON, Volume II

Cappelens Forslags konversasjonsleksikon, bind II (Cappelens Forslags Conversational Lexicon, Volume II) is an anthology in the form of a subjective encyclopedia, written by 83 authors and artists from around the world. The Lexicon contains several hundred articles defining words, things, places, people and emotions in the style of a conventional encyclopedia, though the articles contained in it all share the trait of being unGoogleable and entirely in disagreement with conventional truths. The non-Nordic authors writing in this volume are presented in both their native language as well as in either English and/or Norwegian translation. As the majority of the contributors are Scandinavian, the book is fully understandable only to readers fluent in both the Scandinavian languages and English. Many of the articles are in English, though, and the book has a color-coded pagination system alerting English speakers to texts in that language. There's a good amount in German, too. Macedonian, Irish, Icelandic, Russian, Afrikaans and Danish pepper the pages. There's even a page in braille, bringing the number of languages present in the book to 11. As a commercial animal, it should clearly be taken behind the shed. But then common sense never applied.

Among works by a slew of Scandinavia's finest writers, artists and poets are articles by top shelf international literary and musical talent such as authors George Saunders, Jonathan Lethem, Ransom Riggs and Ron Currie, Jr., cult heroes Craig Clevenger and Soren Narnia, photographer Catherine Chalmers, as well as musical icons Blixa Bargeld, Jarvis Cocker, Michael Gira and Rennie Sparks. The European contingent counts great writers like Germans Wladimir Kaminer and Tilman Rammstedt, Irish John Kelly and Belinda McKeon, and Macedonian poet Nikola Madzirov. South African Shubnum Khan is the Lexicon's African representative. These writers and artists join the Scandinavian writers due to qualities instantly recognizable in their individual works: a certain adventurousness, pure joy, a willingness to test new waters, and a generosity of spirit. Together the 82 (or is it 83?) contributors and one man publishing house and editor Pil Cappelen Smith create something unique; a book like no other.

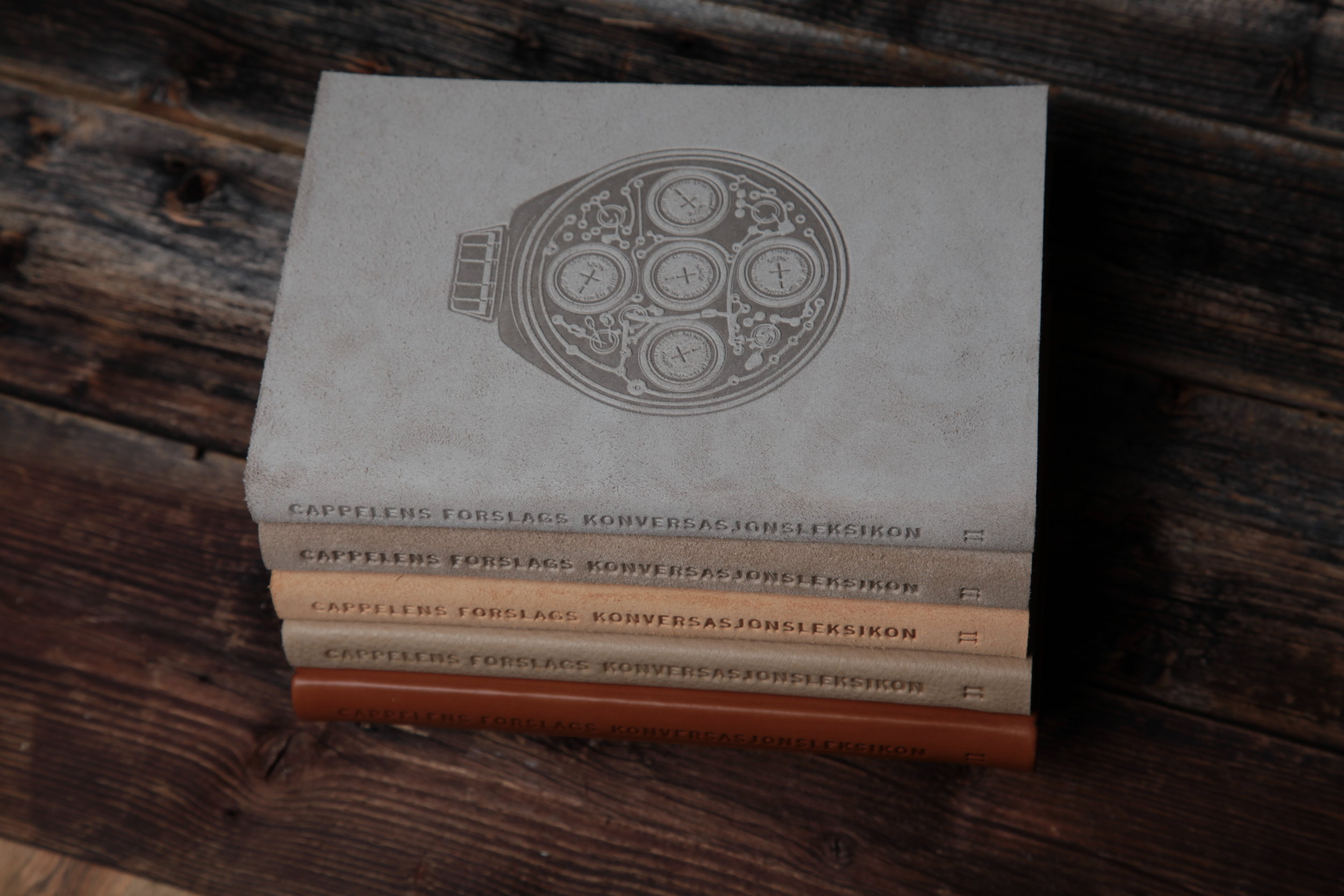

Cappelens Forslags Conversational Lexicon, Volume II was first published in Norway in November 2016 in an edition of 1100 numbered copies, each hand bound in calfskin leather by a third generation bookbinder and with a separate run of 5 numbered copies bound in Icelandic wolf-fish. The book is printed on 150gr. Scandia paper. It was financed by by a crowdfunding campaign that ran in May and June of 2016, which yielded a production budget of €46270, or $48163. The volume follows up on Cappelens Forslags konversasjonsleksikon, a book conceived as a defense of the paper book format as well as a life raft for the independent bookstore Cappelens Forslag. For the full story of the genesis of the series, read on here.

VIDEO: Watch the making of a copy of the book here

Cappelens Forslag's Conversational Lexicon, Vol. I (left) and Vol. II, calf skin hardcover versions.

Cappelens Forslag's Conversational Lexicon Volume II, calf skin soft cover versions.

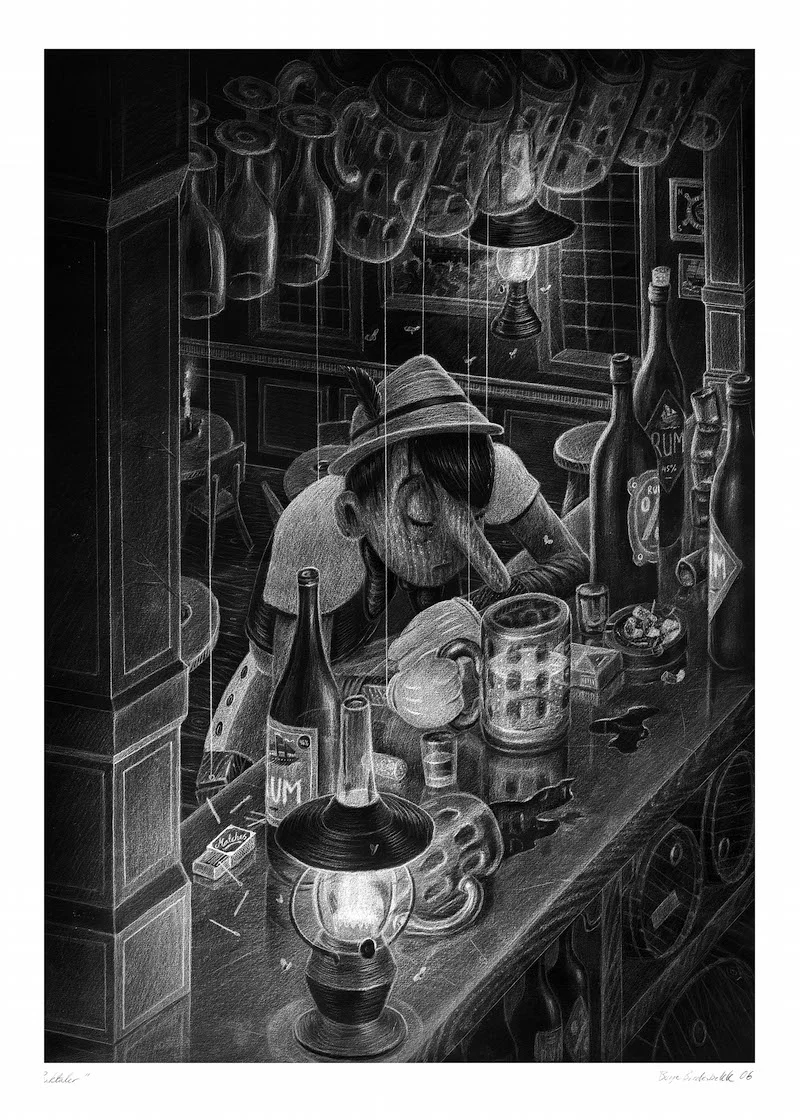

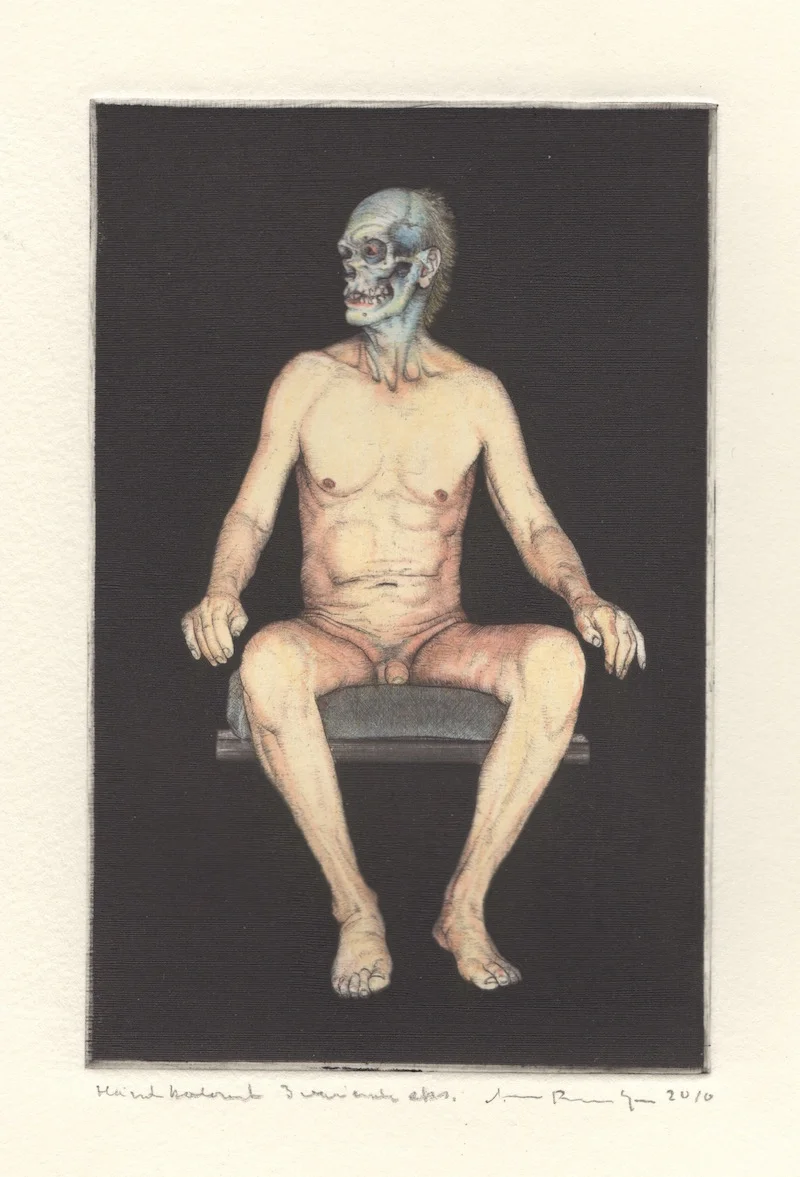

A taste of text: Here are some examples of texts and images from the pages of CFKL Vol. II.

1977, in 1977 we were old. The tall ships had left the harbour. Muhammad Ali lost his crown to a kid who used to shake you down for spare change on the corner of Smith and Bergen. The president told us to turn down the heat and wear a sweater. Pink Floyd toured with an inflatable pig. It was okay. Somewhere, someone was translating Metal Hurlant from French to English. Brian Eno was on the telephone with Talking Heads. Muhammad Ali would fight Superman next year, to a draw, and then protect the planet from aliens. The world was old, you were eleven.

– Jonathan Lethem

bliss, often erroneously associated with pleasure, true bliss is more accurately understood as the absolute dissolving of Self. As such, Bliss can only be grasped by viewing the phenomenon of one’s own consciousness through a spotless window of emptiness. Looking at one’s face in the mirror should be the same as looking up at an empty sky. Burning one’s thoughts, desires, hopes, dreams, memories in a cleansing bonfire of Bliss is paradoxically the clear way forward towards union with and dissolution into the rushing river of blissful emptiness from which the erroneous notion of self emerged in the first place, only to double back on itself and erase itself as it creates itself, simultaneously. In this sense, it can reasonably be speculated that our thoughts and our experiences are God thinking us into being. Of course the next reasonable question would be to ask who exactly is thinking God into being? It might be proposed that it is we who bring the Divine Presence into being by thinking, while inside that timeless instant God negates us and God’s own thoughts at once, bringing Bliss. In this sense Bliss can be understood as the absence of everything, or the space between or before everything, or the emptiness out of which all phenomena emerge, simultaneously disappearing in the instant they are apprehended, imagined or conceived. Bliss = Absolute Emptiness, which is both crucial and impossible to conceive.

– Michael Gira

Spontaneous Incorporeal Sentience (SIS), a fringe theory of astrophysics which proposes the existence of randomly generated, self-aware signals throughout the universe.Proponents of the theory first point to the age of the universe (between twelve and fourteen billion years), and the multitude of celestial bodies within the universe that emit one or more forms of electromagnetic radiation—approximately 100 billion stars and 100 million black holes (at the event horizon)— along with the multitude of bodies that might block, distort or otherwise interfere with the wavelength and direction of that radiation (including other stars and black holes). Citing the infinite monkey theorem, proponents believe that over time the abundance of signals combined with the interference and intersection of those signals will produce apparently meaningful data by random chance.A simplistic analogy—proffered by critics who call SIS the Invisible Space Monkey Theory—likens this to recognizable words accidentally appearing in alphabet soup. But advocates of the theory stress that it is far more complex; more akin to producing the binary-code equivalent of a DNA strand from an infinite number of coin tosses (an analogy that does the theory no favors, according to some).

Further, SIS proponents cite the commonly held belief among experts in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) that intelligent, self-aware programming is largely a question of scale; i.e., that for an intelligent machine to be aware of its own existence requires an immensity of computing power that is only recently within the realm of possibility. With the immeasurable number of spontaneously-created meaningful signals, say SIS advocates, it is likewise a question of probability that one of these intelligent vector points (IVP’s) is both large and dense enough to also be self-aware. In short, SIS proponents are suggesting the random and spontaneous generation of artificially-intelligent code from the noise of deep space. Critics of SIS theory point out that even with the infinitesimal probability of such an event happening, the event itself would be so brief as to only be measurable in fractions of a nanosecond, thus of no significance to the field at all. Proponents counter that events measured in nanoseconds are indeed significant, and that the field of quantum physics would not exist without them. Furthermore, according to the theory of relativity, a nanosecond event light years away might take decades or longer to transpire when observed from Earth. In short, an intelligent, self-aware and non-corporeal entity would, to its own self seem eternal.

Still other scholars have suggested that the appearance of the burning bush in the Book of Exodus is an example of an SIS manifested (against spectacular odds) on our own planet. The first expression of an SIS newly aware of itself would be that of its own awareness, hence, “I am who I am.” (Exodus 3:14) Such scholars also state the spontaneous combustion of the “burning bush” is evidence of a brief confluence of radiation, further supporting their claim. While the theory remains hotly contested and without widespread acceptance, it is nonetheless gaining traction among younger academics who are quick to point out that self-aware intelligence, whose existence is relatively fleeting but nonetheless believes itself to be the center of creation, is not without precedent in the universe.

– Craig Clevenger

ventriloquist, a person inordinately fond of a puppet. This relation is often dysfunctional and may become abusive. This psychological condition may become so pronounced that the “ventriloquist” will claim to be speaking for the puppet. The puppet will have no means of refuting this charge. – I’m not a puppet, I am an independent being! the puppet will say, and the “ventriloquist” will, at that precise moment, move his mouth, just a little, so that it looks like he is trying and failing not to move his mouth at all, i.e., so that it appears that it is him, the “ventriloquist” speaking, and not the puppet. No matter how much the puppet protests, the wily “ventriloquist” will continue to claim credit. – He’s a liar! the puppet may cry. – It is me speaking, not him, and I do not need him to pull those strings in order to move my arms and legs, as I am right now, this moment, doing! And the crowd will roar with laughter. Only late at night, when the puppet (commonly and pejoratively referred to as “the dummy,” by the “ventriloquist,” as part of his ongoing attempt to maintain hegemony over the puppet via ritual humiliation) has been imprisoned inside his (or her) coffin-like holding apparatus, will the puppet be allowed to speak without the “ventriloquist” claiming credit for it, because the “ventriloquist” is up in the hotel bar, drinking away his shame at the outrage he is nightly committing. – I am me, the puppet may softly say. – I am me, no matter what. But there is no one to hear, except an elderly janitor – only too bad, the janitor is old and nearly deaf, and the puppet is speaking so very softly.

– George Saunders

Ventriloquist – Børge Bredenbekk

deconditioning, human beings have no influence over which country or what age they are born in. They are born into already existing structures and must adapt to these conditions. If they grow up in Munich they must enjoy Oktoberfest and master yodelling; in Russia they must drink warm vodka from large glasses and these days also love Putin; in India, cows are worshipped. But when a Munich native chases cows in India blissed out on vodka, then he is deconditioned.

– Wladimir Kaminer

dawdle, (pronounced doordul) The key to a good word is fine, rounded sounds. Say this word & you can feel very pleasant vibrations in your sinuses. A fine brandy of a word. I dislike abrasive short words like gig, tit & (worst of all) Brit - ugh: they’re like chewing on tin foil. No pleasure whatsoever. You might as well just spit at the person you’re saying them to. Which is rude. Dawdle means to take a long time to get where you’re going. Which is the way I prefer to travel through the world.

—Jarvis Cocker

hibernation, every year in November we can finally start preparing for hibernation. We find a cosy cave. We cover ourselves with leaves. We set our cell phones to flight mode. We enjoy ourselves under the leaves, the rustling sound, everything filled with anticipation. Sometimes we'll nod off, but never for long enough, just not for long enough; when we leave the cave it is still November. There are withered leaves in our hair and zero missed calls on the cell phone.

– Tilman Rammstedt

Graphochord, the, a hybrid typewriter/musical instrument invented in 1890 by The Reverend Horace Tiplady – a Church of Ireland clergyman, amateur harpsichordist and author of numerous Gothic romances. Born in Clabby, County Fermanagh on May 5th 1861 he trained for the ordained ministry in Dublin and thanks to the influence of his father, by then the Dean of Lismore, he obtained the curacy of Ballyhaise, County Cavan – a quiet, uncomplicated spot where he resided for the rest of his life, working obsessively on his extraordinary machine.

An eccentric and driven man, the Reverend Tiplady believed that words and music were intimately connected, and that individual letters and combinations of same bore a direct relationship to musical notes. Consequently he conceived of a machine that would receive typewritten information and immediately “translate” that information into music. That his machine worked in quite remarkable ways there is little doubt, but as no model survives (as far as we know) we must accept his own testimony that it sounded “rather like a muted harpsichord” – from which we might further deduce that it sounded somewhat like a toy (or a prepared) piano. As to its appearance we must assume not only percussive keys but also the stringed element suggested by the term chord. The manual typewriter, a revolutionary 69 instrument in itself, had been invented by Christopher Sholes 1819 and during the period of Tiplady’s research, many machines were already in circulation. One of the first (an 1874 Remington) was owned by Mark Twain who claimed to have used it to write Tom Sawyer, published in 1876. That said, the first typewritten manuscript he actually delivered was Life on the Mississippi in 1883. Nietzsche had purchased a machine known as a writing ball the year before, and Tiplady’s – the same make as Nietzche’s – was shipped from Denmark during the harsh winter months of 1889. In his drawing room in Ballyhaise, Tiplady immediately set about adapting the newly arrived skrivekugle to his purposes. We cannot be entirely sure of his manipulations and adjustments as he was notoriously secretive about the process – in particular as to how letters, notes or chords might be synchronized – but we can speak with some authority as to his intentions. In Graphophony & The Divine Arts: Or, A Short and Easy Treatise on that Subject. (London, 1894) Tiplady outlined his grand ambition – to “render audible, to the Glory of God, the hidden music of the Scriptures.”

Early experiments were met with astonishing, if confusing, success. According to his own account, it was discovered that passages of the Book of Genesis, when typed into his adapted writing ball, sounded uncannily like elements of Bach’s Die Kunst der Fuge, and that the words of several well known hymns translated themselves into certain airs he had often heard played by “the more skilled of the fiddling peasantry.” But for the most part however, Tiplady conceded that much of the music produced by his machine was an “interesting but distressingly cacophonous fury of sound.”

The tragedy in this conclusion however is that Tiplady, being a man of is time, was entirely unaware of musics yet to come and it now seems entirely plausible to the modern music enthusiast that the early books of the Old Testament so beloved of Tiplady, may well have yielded notes similar to those in Book III of Bela Bartók’s Mikrokosmos or indeed certain piano works of György Ligeti. Tiplady’s own descriptions of the music would certainly support such claims.

The Reverend Horace Tiplady died at his home in Ballyhaise on September 24th 1895. The Graphochord was not found among his belongings and his housekeeper allegedly stated that, in frustration, he had, some days previously, destroyed it by brute force and flame. Others however maintained that, on the very night of his death, he had been seen pushing a “heavy four-legged item” into the River Annalee, a tributary of the Erne – a persistent claim that has led, in recent years, to increasing pressure on the Irish Government to make a concerted attempt to retrieve the machine so that proper research might be carried out into its workings and possibilities.

The Reverend Horace Tiplady is buried in his native Clabby, County Fermanagh. The inscription on his gravestone reads: Man of God – Musician – Author – Inventor.

– John Kelly

face, the front of the head, where facial expressions occur. – His dead f. is cold and white. It’s stiff. Nordic. It is terrifying. It is death. The skin is waxlike, hardened. This is just a f. Nothing about the cheekbone, forehead, nose reveals anything about who he has and hasn’t been. If contemplated in and of itself, it’s just a f., one of the world’s many f.-s, dead. It’s just cold and white, and stiff and terrifying, it is horror incarnate: it is death. His f. is death. Yet the worst thing about the face isn’t death, when he opens his eyes and looks at us, the worst thing isn’t that the face is dead, the worst thing is that it is alive. That his dead f. is alive.

– Gunnhild Øyehaug

Face – Arne Bendik Sjur

ghosts, entities that don’t exist until you say the word, “Ghost” or even think it in a quick whisper inside your head. This simple slip of the tongue gives life to the air, creating huge howling demons that suckle endlessly upon your every thought and word. See especially old men in torn green windbreakers sitting in coffee shops for hours pretending to drink from a cup found in the trash. These are the half-devoured ones, caught between this world and the next. If they should whisper the word, “devil” or merely think the first syllable —‘dev’— they will be taken in an instant, away into the darkness that gathers at the top branches of long dead oaks. Here they become the howling wind, the empty night, the hungry air itself.

– Rennie Sparks

jazz clarinet, the most celebrated instrument in popular music from the mid 1920’s until June 6th, 1952, at which point it became not just passé, but completely unbearable. In a matter of days both Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw were tarred-and- feathered before intermission, and Sidney Bechet was forced to hide in the sewers of Paris, where he would reside for three years. Musicologists have offered varying theories as to what caused such a violent reversal. Some cite atmospheric changes — increased humidity, a shift in the jet-stream — that govern the precarious acoustic border between clarion and screechy. Others blame nuclear fallout, while certain crackpots are positive that the answers are sealed in a bunker beneath Area 51. A more useful line of inquiry, however, is not to ask why the jazz clarinet ceased to be popular, but why this shrill, cloying instrument was ever popular in the first place. Perhaps the demise of the jazz clarinet was less a paroxysm than a merciful correction; the breaking of a strange collective fever.

– Yoni Brenner

dust, ordinary house dust consists of 80% dead skin cells, all containing your DNA. We’ve all had the experience: You come home late one night, and just as you’re about to switch the light on you sense someone standing in the room’s darkest corner, someone who maybe looks a lot like you. When you ask them what they want, their only reply is a cough; turn on the light and they disintegrate.

The following morning you look around, thinking it’s been ages since you cleaned the place.

– Knut Nærum

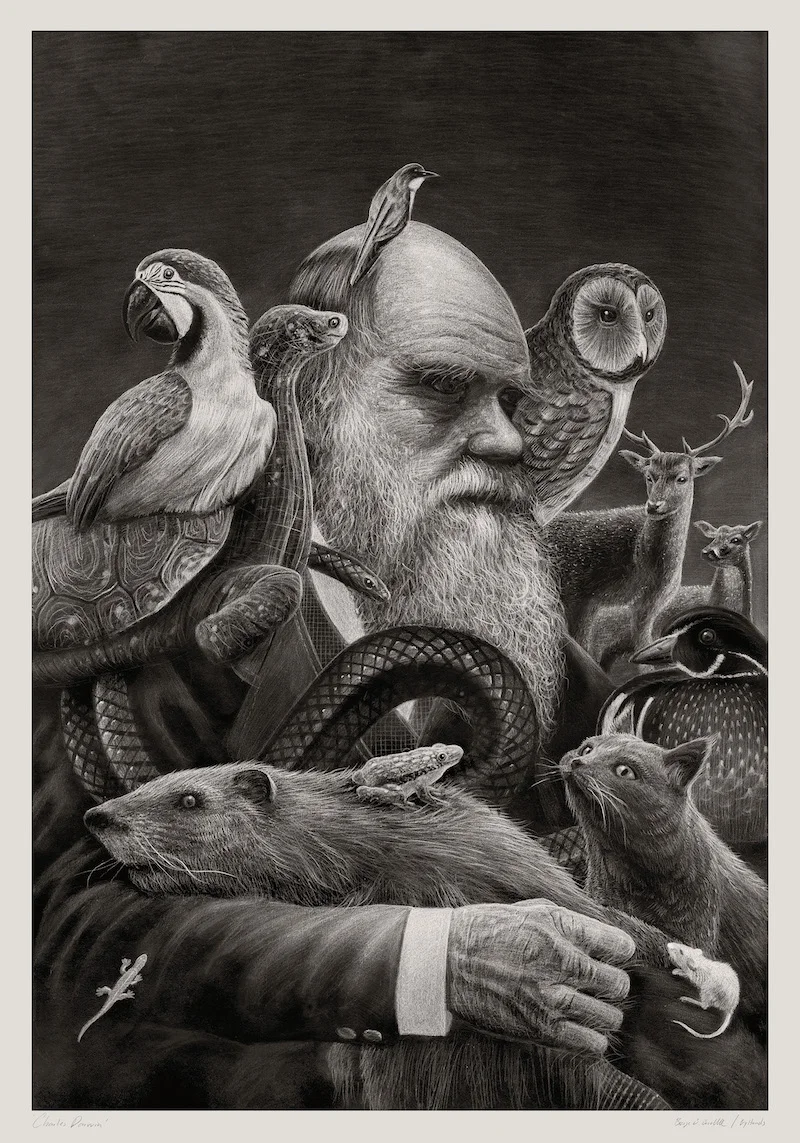

darwinism, diagnosis. Known to cause melancholia, feelings of purposelessness and an intense longing for a lost sense of mystery.

— Pil Cappelen Smith

Darwinism – Børge Bredenbekk

The Scandinavians:

Atle Antonsen

Arne Bendik Sjur

Aslak Dørum

Arild Fröhlich

Amalie Kasin Lerstang

Aleksander Melli

Arild Rossebø

Børge Bredenbekk

Bård Breien

Bår Stenvik

Bård Torgersen

Didrik Morits Hallstrøm

Didrik Søderlind

Egil Hegerberg

Eivind Hofstad Evjemo

Eigil Jansen

Endre Ruset

Eskil Vogt

Frode Grytten

Gine Cornelia Pedersen

Gunnhild Øyehaug

Hanna Dahl

Hilde Susan Jaegtnes

Hilde Østby

Imac Zambrana

Jeppe Brixvold

Jan Grue

Joanna Helander

Josefine Gråkjær Nielsen

Johan Harstad

Joakim Kjørsvik

Kurt Aust

Kim Hiorthøy

Karine Nyborg

Kjersti Annesdatter Skomsvold

Knut Nærum

Kristina Stoltz

Knut Åsdam

Lina Breidablik

Linda Klakken

Lars Lønning

Lars Petter Sveen

Marius Asp

Marianne Kaurin

Mímir Kristjánsson

Madame Nielsen

Morten Strøksnes

Mathilde Walter Clark

Nikolaj Frobenius

Ola Jostein Jørgensen

Ole Robert Sunde

Pil Cappelen Smith

Peter-John DeVilliers

Rein Aarek

Rune Christiansen

Roskva Koritzinsky

Sternberg

Sigmund Doksum

Synnøve Macody Lund

Terje Dragseth

Torgrim Eggen

Tommy Olsson

Øivin Horvei

Øyvind Kvalnes

Back to top

Reviews & articles in English, German, French, Italian, Spanish, Danish, Norwegian :

Spain: Perdiz / Diccionario conversacional: una enciclopedia subjetiva (Spanish version)

Perdiz / Conversational Lexicon: A subjective encyclopedia (English version)

France: ActuaLitté / Une librairie norvégienne crée une encyclopédie subjective

UK: The Guardian / George Saunders and Jarvis Cocker help turn 'freak of publishing nature' into hit

UK: Routes North / Oslo for Book Lovers

USA: Electric Literature / Would you read a subjective encyclopedia?

Germany: Lesart / DeutschlandRadio Kultur: Universale Welt Sicht In Einem Buch (Universal world view in one book)

Literary critic Peter Urban-Halle discusses CFKL II on the radio channel Deutschlandradio Kultur's literary magazine Lesart. Norwegian translation at the bottom of this page.

Switzerland: Neue Zürcher Zeitung / Wann ist eigentlich nie?

Italia: Barta / Patafisica Lessicale

Denmark: Weekendavisen / Perfekt Defekt Konfekt

Norway: Dagsavisen / Løgn og leksikalsk bedrag (Lies and encyclopaedic deceit)

English translation below:

Dagsavisen: Lies and encyclopaedic deceit

Crowd funded enlightenment has rarely been as mendaciously amusing as in «Cappelens Forslags Conversational Lexicon, Vol. II».

Pil Cappelen Smith (Ed.)

«Cappelens Forslags konversasjonsleksikon, bind II»

Published by Stort Forlag

“Satire: the kind of humour that is funny if you agree.” The definition is Knut Nærum’s, forever inculcated in «Cappelens Forslags Conversational Lexicon, Vol. II». The definition may also double as a mantra for one of Norway’s most unlikely book successes; a conversational lexicon in which the novelty value far surpasses any actual usefulness. As with the first volume which appeared in 2014, volume II is a conversational lexicon for lovers of the word, the whimsical, and for those who can´t get their fill of exquisite book binding or humour of the kind Nærum describes.

The kind that’s funny if you agree, and apparently a great many are.

A number of those are also contributors to Pil Cappelen Smith’s brilliant book project; an outright rescue plank bound in calfskin, based on crowd funding and willing pen pals supplying articles on a whim, rallying around the strange beast that is the independent bookstore Cappelens Forslag, so that it may continue supplying new and used quality literature to the little masses.

Volume I, published in 2014, became a formidable success, reprinted in several editions of more or less exclusive character and still available in a reasonably priced paperback. Volume II follows the recipe of the first volume, and excels through a composition of contributors which is more international than in the first book. One of the most interesting names in this respect is Blixa Bargeld, uncontested band leader of Einstürzende Neubauten and former guitarist in Nick Cave’s The Bad Seeds. Jarvis Cocker of Pulp and Swans-boss Michael Gira are also on the exclusive list, along with, among others, Danes Madame Nielsen and Jeppe Brixvold, and Norwegian cultural notabilities like Atle Antonsen, Rune Christiansen, Roskva Koritzinsky, Gunnhild Øyehaug, Johan Harstad, Ole Robert Sunde, Nikolaj Frobenius and filmmaker Eskil Vogt.

On their own, and in collusion with editor Smith, the writers nurture their own linguistic peculiarities and idiosyncratic humour, often satirical, often devious, sometimes a wee bit snarky. Like author Frode Grytten’s definition of Hivju, Kristofer (Norwegian actor portraying Tormund Giantsbane on Game of Thrones, transl. note):

“Concept developed by Innovation Norway for global dissemination of Norwegian core values such as get-up-and-go, authenticity, strength of character and ginger facial hair.”

The most rewarding texts are often the longer ones, like Ole Robert Sunde’s strongly subjective stories (on such things as Smalahove (salted, smoked and dried sheep’s head, a traditional dish, transl. note), or when Ola Jostein Jørgensen holds forth on his aforementioned colleague in “S, writers starting with”. In this way Cappelens Forslags Conversational Lexicon, Vol. II becomes the obvious “missing link” between the intellectual and cultural domains, the latter of which is the opposite of the former as, posited in a text by Torgrim Eggen that undresses conventional truth in a manner that showcases the Conversational Lexicon’s true value; where the humour contains enough recognition to become a truth in itself. Like in the sparkling, liberating designation of the day Sunday: “The nakedest day”.

Cappelens Forslags Conversational Lexicon, Vol. II is not least a book with great appeal to those of us who appreciate books as aesthetic object beyond their content. Julius Ørenberg Bookbinders’ calfskin binding of the first 1100 copies is a joy to behold, and the layout of text and illustrations borrow nostalgic patina from the classic lexica, spiced up with vignettes and contributions from among others Arne Bendik Sjur. An anatomical pop-up illustration and a page in braille lifts the book’s ambition and brings the number of languages within it to eleven.

Like most lexica, this is not a book to be consumed in one sitting, from A to ÆØÅ. It is best enjoyed in small measures. To say it with Ole Robert Sunde’s definition of a raw, good, unsentimental grappa, without silly ice cubes: “It must be imbibed with cool passion”. So, too, should one read Cappelens Forslags Conversational Lexicon.

–Mode Steinkjer

DeutschlandRadio Kultur / LESART: "UNIVERSELL VERDENSANSKUELSE I ÉN BOK":

Programleder: I Norge er det utkommet en svært forbausende bok; en bok som kan virke som om den er falt ut av tiden, nemlig et konversasjonsleksikon. Slike leksika ble oppfunnet på 1700-tallet, og skulle opprinnelig formidle kunnskap til bruk i velpleid salongkonversasjon. Salongene finnes ikke lenger, og leksika er også et utdøende format i Wikipedias tidsalder. Altså, hvorfor utgir man i Norge i dag et nytt, dyrt Cappelens Forslags konversasjonsleksikon?

Spørsmålet går til Peter Urban-Halle, som har befattet seg med boken.

Peter Urban-Halle: Ja, dette er jo ikke et nytt Brockhaus (klassisk tysk encyclopedi, overs.anm.), det er ikke bare rappet fra gamle leksika og oppslagsverk; det er et spesielt leksikon. Det fins naturligvis forbilder – jeg tror man har orientert seg etter Diderots berømte encyclopedi

Programleder: Fra opplysningstiden…

Peter Urban-Halle: …nettopp, som ble publisert for 250 år siden. Bidragsyterne var berømte folk fra Diderot selv via Rosseau til Voltaire. Oppslagsordene var delvis av generell interesse: hva er magi? Hva er utroskap? Det er det vi alle er interessert i. Oppslagsordene var delvis meget spesielle: Hvem er det som resonnerer om snorking, eller tårnfrisyrer? Videre fins det er forelegg i Danmark, med Brøndums Encyklopedi som utkom for 20 år siden. Men dette norske leksikonet er for det første mye mer omfangsrikt, og så har det internasjonale bidrag og forfattere: fra de nordiske landene og USA og Tyskland.

Programleder: Og disse skriver også om utroskap og snorking da, eller hvilke temaer skriver de om?

Peter Urban-Halle: Både og. De fleste er svært subjektive; tankeoverføring, søvngjengeri, paraply, for eksempel. Det spesielle er at forfatterne selv har vært med å foreslå sine oppslagsord, for så å snakke, tenke og resonnere omkring dem på en meget personlig måte. Kanskje vi kan se på de tyske forfatterne, det interesserer oss vel mest: Det er Tilman Rammstedt, Wladimir Kaminer, begge forfattere, og – overraskelse – Blixa Bargeld, grunnlegger av Einstürzende Neubauten, som forøvrig skriver om Godzilla, som i hans tekst er kvinnelig, og ødelegger Unter den Linden fra Brandenburger Tor helt fram til Potzdamer Platz. Det passer jo bra til navnet Einstürzende Neubauten, sannsynligvis. Rammstedt synes jeg er meget interessant. Han skriver bl.a. om Kilde.

Hva er en kilde? Det kan jeg jo lese høyt, det er svært kort:

kilde, det finnes pålitelige kilder og upålitelige. Fra de pålitelige springer det natriumrikt vann eller en kjent elv. Fra de upålitelige springer det gode historier.

Det syns jeg er skrekkelig gøy, siden han leker med den konkrete og den overførte betydningen av ordet kilde. Kaminer, veldig lattermildt om dekondisjonering – kanskje et moteord – han går ut fra at alle mennesker er vokst opp med en bestemt kondisjonering: Med en fra München tenker man på Oktoberfest; med en russer tenker man på vodka, og med en inder på ku-tilbedelse. I siste setning i hans bidrag lyder det:

Når en vodkasalig Münchener jager kuer i India, da er han dekondisjonert.

Programleder: Fine eksempler. Lattermildt, som du sier, i hvert fall Kaminer, men også Godzilla, på sitt vis. Er det hele en stor spøk, dette leksikonet?

Peter Urban-Halle: Ja, tuller de bare når de fremviser skråblikk på ulike temaer? Vi må spørre oss: Hvorfor gjøre dette? Er det en slags anti-leksikon, som det faktisk ble skrevet i en anmeldelse, og hvem er tjent med å utgi et ikke-leksikalsk leksikon?

Programleder: Ja, hvem er tjent med det?

Peter Urban-Halle: Spørsmålet er: hva er verdien av hele greia? Da vender jeg tilbake til Diderot, som da han jobbet med sin encyklopedi skrev til Voltaire: Vårt slagord lyder: Ingen nåde for fanatikere, fjols og tyranner!” Dette var, som du allerede har sagt, i opplysningstiden. Den gangen raste en offentlig krangel om leksikonet. Slik er det jo ikke lenger; ingen konge vil forby et slikt leksikon, og da slett ikke den norske kongen. Likevel ser jeg i denne boka en Diderotsk encyklopedi for vår tid, fordi den beskjeftiger seg med frie tanker. Alene det at leksikonet ble publisert i fysisk format er en motstandshandling. Her skrives det mot internettets globale konsensus – mot Google, mot Wikipedia. Jeg ser frem for alt en glede over den tematiske frihet og over subversiv tenkning, altså en tenkning uten grensesetting.

Programleder: Og hva betyr subversiv tenkning for deg, slik den fremstår i dette leksikonet?

Peter Urban-Halle: Flere av oppslagsordene utfordrer, og lokker frem satire; Erdogan, for eksempel. Men for å bli litt mer seriøs: I første bind finnes et motto i innledningen:

Und dann und wann ein weisser Elefant. Sitatet er faktisk fra diktet Das Karussell av Rilke – det er inntrykk av øyeblikket der gjenstander blir symbolske, og her i leksikonet er det subjektets inntrykk som også kan inneha en symbolsk dimensjon som peker utover subjektet selv. George Saunders, for eksempel, den amerikanske forfatteren, skriver om buktaler. Det er også veldig vakkert, og legger ut om den psykologiske relasjonen mellom buktaleren og hans dukke – hvem er egentlig hvem, og fremfor alt, hvem er jeg’et i denne relasjonen? Det er en overraskende refleksjon, og det er artig, i likhet med de fleste oppslagsordene i dette leksionet.

Programleder: George Saunders kjenner jeg som en storartet novelleforfatter, man bør lese alt han skriver.

Peter Urban-Halle: Ja, presis.

Programleder: Før var slike leksika dekorative utrustningsstykker; de stod i hyllene og demonstrerte helst lærbunden dannelse i lange rekker. Dette leksikonet finnes også i luksusutgave, hvordan er den laget?

Peter Urban-Halle: Jeg vet ikke hvor mange som den gang hadde råd til Diderots leksikon, sikkert ikke så mange som har råd til denne boka i dag. Men produksjonen er spesielt utsøkt. Første bind kom i 1100 eksemplarer, i fire forskjellige skinntyper, og mer eller mindre eksklusive utgaver; håndbundne. Første utgave ble utsolgt på en uke til tross for den høye prisen, nå finnes andre bind i tre luksusutgaver (steinbitbundne eksemplarer, overs.anm.). Også de er nå solgt, selv om de koster 1000kr stykket(€1000, overs.anm.).

Programleder: Og ble ikke det første eksemplaret stjålet fra butikken med det samme?

Peter Urban-Halle: Denne anekdoten passer virkelig til hele leksikonet. Det første eksemplaret i det første opplaget ble stjålet om natten den 24. oktober 2014 fra butikken. Da var boka ikke en gang på markedet, den var ikke i bokhandelen, men et eksemplar ble stjålet. Som følge av dette –

hva gjorde redaktøren? Han preget de siste 1099 eksemplarene med et stempel pålydende:

Denne boka ble ikke stjålet 24. oktober 2014. Det betyr at den som finner en bok uten dette preget vil vite at dette er det stjålne eksemplaret.

Programleder: Et i hvert henseende kuriøst bokprosjekt. Det likte du tydeligvis, men nå kan vel du forstå norsk, noe jeg ikke kan. Hva skal vi andre gjøre, bortsett fra å lære oss norsk?

Peter Urban-Halle: Ja, man må vel kunne litt engelsk, fordi det finnes tekster på engelsk – Ron Currie, den amerikanske forfatteren, Junior forresten, skriver om Death, om døden, jeg tror faktisk det er bokens lengste tekst. Jeg hadde likt å lese den på norsk, som jeg på en pussig måte kan bedre enn engelsk. Men noen tekster er på tysk, og hvem vet – kanskje vi snart kan lese det hele på tysk?

Denne boka er morsom og utfordrende nok til å bli oversatt.

Programleder: Cappelens Forslags konversasjonsleksikon: første bind kom i 2014, det var utgaven hvor første eksemplar ble stjålet, og i slutten av november kom bind to – vi venter på den tyske oversettelsen. Tusen takk, Peter Urban-Halle.

More reviews in other languages will be added as they appear.